![]()

71

- Sudden Fiction Latino, edited by Robert Shadard, James Thomas and Ray Gonzales

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Roberta Skloot

- This Party’s Got to Stop by Rupert Thompson

_______________________________________

Sudden Fiction Latino: Short-Short Stories from the United States and Latin America; edited by Robert Shapard, James Thomas, and Ray Gonzalez.

Sudden Fiction Latino: Short-Short Stories from the United States and Latin America; edited by Robert Shapard, James Thomas, and Ray Gonzalez.

W.W. Norton & Company, New York, June 2010.

The very rich are different from you and me, yes. That line sprang to mind as I realized how very different as well is Latin America literature, be it from Latin America or descendants in the U.S. who draw from their roots. In this superb collection of 60-plus short-short stories (all under 1500 words), we see a literary tradition far different from what we are accustomed to, a literary tradition that draws on historical precepts different from our Euro-American heritage. There is a music in the prose, be it a translation or not, that strikes a new chord. We are on fresh ground in these stories; they dazzle and surprise, creep up on us in a collective way and leave us amazed. Yes, Latinos are very different from you and me. And that is good. They form a beautiful part of the mosaic to which we all contribute, to which we all belong.

Here, there are stories of border crossings (Fernando Benavidez’s “Montezuma, My Revolver”); earthquakes that expose mysterious crypts (José Emilio Pacheco’s “The Captive”); and one of advice to young men (Lupe Méndez’s “What Should Run in the Mind of Caballeros”), which reads rather like a Latino commencement address: “Don’t start fights, just end them / stand up for yourself . . . a little / mind your own business / never touch the ball with your hands / play fair / no name-calling / no swearing, remember you pray with that bocota of yours / let ladies go first / open doors for everyone / don’t stare at her . . . with your mouth open . . . .”

There are stories, of course, that hint of evil regimes and how they have damaged those who lived through them (Isabelle Allende’s “The Secret”); and of those who are at the mercy of figures lurking the dark (Pedro Ponce’s “Victim”); as well as a peek at the domestic abuse that lurks in machismo culture (“Aunt Chila” by Ángeles Mastretta). Injustice and abuse know no borders, yet it is the strength and resiliency of its victims that impress us here.

Included is a fantastical piece by the master, Jorge Luis Borges, “The Book of Sand,” with its infinite number of pages. There is, too, the lush and lovely magic realism which infuses so much of Latin American literature: Gabriel García Márquez’s “Light is Like Water” explores the fantasy of childhood play; while Carmen Naranjo’s “When New Flowers Bloomed” tells the tale of a village where all the women become pregnant.

In contrast there is the voice of Chilean exile Roberto Bolaño who turned his back on the magic realists and sought new terrain as can be seen in “Phone Calls,” which inspires us to look more attentively at the world.

Uruguay’s Eduardo Galeano’s “Chronicle of the City of Havana” tells of a young man who travels from Los Angeles to his homeland of Havana where he hasn’t been since his infancy and where he gets a mesmerizing dose of Latino machismo that is simply funny.

There are parables, such as Rudolfo Anaya’s “The Native Lawyer”; and moral tales, such as Daniel A. Olivas’s “La Guaca.” I love the way the latter begins: “There was a man who owned the finest restaurant in the village. Though no name adorned the establishment, the villagers dubbed it La Guaca, the tomb. The man, as well, had no name . . . .” We pretty well know we are set up for a moral tale; yet, it is . . . different.

Exile, of course, forms another theme. There is Uruguay’s Cristina Peri Rossi’s “The Uprooted”: “You see them frequently, walking down the streets in big cities, men and women floating on air, suspended in time and place. Their feet lack roots, and sometimes they even lack feet. Their hair doesn’t have roots, nor do they have soft vines to tie their trunks to any type of ground.” And Peru’s Julio Ortega’s “Migrations” in which the language barrier is addressed: “My English is merely Spanish making its way across the dubious sea of translation – that other migratory condition of naming.”

So many, many stories, I can’t begin to recount. This is a treasure of an anthology and will take you to new places. If you’re Hispanic, it will read more familiar, but just as luscious. Somos iguales; somos diferentes. ¡Viva la diferencia en un mundo sin fronteras! J.A.

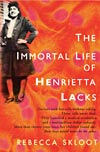

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacksby

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacksby

Rebecca Skloot;

Crown, 2010

I had two misgivings about writing this review: one, why would a reader of The Barcelona Review be interested in a non-fiction book about a science story, when TBR has a reputation for “potent, powerful, and cutting-edge fiction”; and two (full disclosure), I am a science-impaired learner and feared that I could not do justice to the phenomenally important science side of this amazing story.

As it turns out, not to worry. I could put this gripping true account of Henrietta Lacks and the Lacks family right up there with any potent, powerful and cutting edge story TBR has for us; PLUS, Rebecca Skloot has a compelling gift for weaving story-telling and scene-construction with the most comprehensive scientific information in a way that makes it accessible and yes, even fascinating, to a science phobe.

So! After ten years of meticulous and dogged research, investigative reporting and writing, Rebecca Skloot takes us on a harrowing nail-biting ride with Henrietta Lacks and her family, particularly her daughter, Deborah. It begins with characteristic curiosity in a college biology class in 1988, on being told that the “HeLa” cells used for much of medical and scientific research on diseases and their causes and cures came from one black woman named Henrietta Lacks, who died of cervical cancer in 1951. Rebecca wanted to know: Who was Henrietta Lacks?”As Deborah Lacks says to her a long time later, after refusing to talk to her for nearly a year, “Get ready, girl...You got no idea what you gettin yourself into.”

The book has layers and dimensions that raise important questions for society, medicine, and science about morality, ethics, justice and compassion in biological research using human material, as well as a continuous theme of irony (“Show me the money!”)

Henrietta Lacks was a poor, uneducated, black woman, wife and mother, from a tobacco farm in Virginia, who sought treatment for her cervical cancer at the prestigious Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, in the “Colored Wing," at a time when many hospitals did not admit blacks. Shortly before her agonizing death on October 4, 1951, a sample of her cancerous tissues was taken without her or her family’s knowledge or consent, a formality unknown at that time. Until that time, cells in tissue samples kept alive in a culture medium would live briefly, then die, but Henrietta’s “HeLa” cells lived and grew, becoming the first “immortal cells,” expanding and multiplying from then to the present, and have been used worldwide in medical and scientific research on cancer, polio, viruses, fertility, cloning, and in many other areas.

Meanwhile, the Lacks family, living in impoverished circumstances, and often with medical problems and no health insurance, was unaware of the use or the importance of Henrietta’s cells for over twenty years, until they were approached by a member of a Hopkins research team with a request for blood samples to study their own cells. There were communication barriers of language, education and culture, as the Chinese-born post-doctoral candidate contacted Day, Henrietta’s husband. For Day and the others, the word “cell” was associated with the lock-up where his son was then housed, and the idea of Henrietta being “still living” was inconceivable. There was already a history of suspicion and mistrust in the black community toward the medical establishment, and many stories, rumors, and superstitions about the use of black people in experiments - some well-founded, like the Tuskegee Institute’s horrific syphilis study of black men in the thirties.

Now the Lackses learn that their mother has been “alive” (in cell form) and used in worldwide studies all this time. It is a testament to Skloots' skill as a writer and journalist that for the most part she maintains a cool objectivity and even at times a wry sense of humor as she relates the history of biological practices and issues that today are considered clearly questionable, if not abhorrent, and one chapter is titled “Illegal, Immoral and Deplorable.”

The Lackses had a lot of justifiable anger and resentment at how they were treated, but at one point Deborah says ruefully, “Truth be told, I can’t get mad at science, because it help people live, and I’d be a mess without it. I’m a walking drugstore! I can’t say nuthin bad about science, but I won’t lie, I WOULD like some health insurance so I don’t got to pay all that money every month for drugs my mother cells probably helped make.”

Skloot’s journalistic objectivity shifts dramatically into first-person subjective participation - more like immersion - in the turbulent lives of the Lacks family as she accompanies Deborah on her quest to learn about her mother. Soon after she goes with Deborah and her brother Zakariyya to “John Hopkin,” as they call it, to see where Henrietta’s frozen cells are stored, and to look at them under a microscope (a truly wondrous scene), she goes on a “road trip” with Deborah to learn the fate of her sister Elsie, who was left at an early age at the “Hospital for the Negro Insane” (now the Crownsville Hospital Center). Their discoveries there, including a deeply disturbing photograph of Elsie, trigger the beginning of a downward spiral for Deborah into irrational, erratic behavior and a serious outbreak of hives. When they arrive in Clover, Henrietta’s birthplace in Virginia, Deborah’s cousin Gary, who sometimes preaches and “channels the Lord,” is immediately aware of her agitation and confusion. He soothes her, holds her, sings to her, and speaks to her and the Lord.

At this moment in the book, Rebecca, who already “had us at ‘hello,’” takes us right down the rabbit hole with her in a leap of surrealistic faith:

Looking at me, Gary said, “She can’t handle the burden of these cells no

more, Lord! She can’t do it.” Then he raised his arms above Deborah’s head

and yelled, “LORD I KNOW you sent Miss Rebecca to help LIFT THE BURDEN of them CELLS!” He thrust his arms toward me, hands pointed at either side of my head, “GIVE THEM TO HER!” he yelled, “LET HER CARRY THEM.”

How did we get from scientific research and reportage to channeling the Lord? Because at all times throughout this story, Rebecca Skloot is deft and knowledgeable with her material, and treats her subjects with the utmost, heartfelt RESPECT; respect for their integrity, independence and pride, and for their right and their capacity to learn the full true story of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.

To this day, the Lacks family has received no compensation for the use of the HeLa cells. Rebecca Skloot has established a scholarship fund for the descendants of Henrietta Lacks. Donations can be made at HenriettaLacksFoundation.org

visit: RebeccaSkloot.com

Deborah’s Poem

cancer

check up

can’t afford

white and rich get it

my mother was black

black poor people don’t have the money to

pay for it

mad yes I am mad

we were used by taking our blood and lied to

We had to pay for our own medical, can you

relieve that.

John Hopkin Hospital and all other places,

that has my mother cells, don’t give her

Nothing.

review by Leah Darr contact

This Party’s Got to Stop: A Memoir

This Party’s Got to Stop: A Memoir

by Rupert Thompson;

Granta, 2010

Rupert Thompson first caught my attention with The Insult, a delightfully quirky romp of a novel about a blind man who thinks he can see; then came The Book of Revelation which follows an Englishman’s abduction in Amsterdam by fierce nun-clad ladies who hold him captive. Next came Divided Kingdom, a dystopian novel set in the near future which has England divided according to one’s “humour” (as in one of the four medieval humours, yes); and then Death of a Murder, which follows a policeman’s assigned task of guarding the dead body of one of England’s most notorious murderers: Myra Hindley (unnamed in the novel). The common link, if I may borrow a phrase from Boyd Tonkin, is one “hallucinatory clarity.” Thompson has the uncanny ability to take us completely into the here and now; into a hyper-attentive state that keeps one focused, more like “fixated,” on the moment, as though looking at life through a slightly magnified glass. It can be slightly disorienting even while illuminating. The big picture looms in the background, almost like the elephant in the room that isn’t directly addressed but is unquestionably there; it is delicately held at bay by concentration on particulars, though I in no way mean a fixation on details, but rather, the essentials.

I love reading memoirs by authors whose work I admire. And this particular one does all a memoir should: it gives us the author’s personal history, which in many ways captures the coming-of-age-under-Bowie generation; it allows us a peep at what forms the writer and the creative process behind his work; and, it is one hell of a story.

Thompson’s thirty-three-year-old mother died very suddenly, while playing tennis, when he was eight years old. The book begins: “My mother spoke to me once after she was dead. Nine years old, I was standing outside our house, in the shadow of a yew tree, when I heard her call my name.” Much later, he seeks out this tennis court, now a parking lot, in hopes of finding some closure, or more specifically, in hopes of finding her, for he remembers nothing of the first eight years of his life with his mother. This loss marks him from the beginning, a trauma his brothers escape due to their younger age. His father later remarries, his wife deserts him, and he dies alone in the hospital from a breathing condition he has had since the war. Thompson could have called his father, but did not. These are the bare facts.

The story behind them is something else altogether. After his father’s death, Thompson and his two brothers, now all in their twenties, come together and hole up in the family home for seven months. This particular period forms the core of the book, cleverly incorporating flashbacks and flashforwards which move the narrative nicely along and heighten the suspense, for suspense in one form or another hangs on every page.

The youngest brother, Ralph, comes with a wife and baby. The couple put a huge lock on their bedroom door; no one knows why. They wield flick knives; no one knows why. They are “Catholic” – Ralph converted – though their strange ways smack more of a quasi-religious cult, but no one asks about that either. Thompson and his brother Robin, meanwhile, raid their father’s medicine chest, pop all the pills they can find while guzzling them down with wine from the wine cellar. It is a “last wild farewell” in the family home for these two while the eccentric young brother and wife remain aloof under the same roof. When the house is sold, the two older brothers take an ax to the furniture and burn the pieces in an ongoing bonfire in the backyard. The year is 1984. Thatcher is in office and punk still reigns though Bowie, that icon of the 70s, is the musician of choice. The author has had to leave his current home and German girlfriend in Berlin to help “settle affairs” back in Eastbourne. He almost always wears black.

This second death in the family throws Thompson into thinking not only about his father, for whom he feels guilt over not having contacted, but also about the mother whose memory he has lost. Of his father, he writes to his girlfriend: I still feel very sad about Dad, not deep down, but just under the surface, very large and still, like a reservoir.

There will be trips to various people in hopes of reviving his parents, particularly his mother – including an excursion to see an unhinged old uncle, who once made it big in South America before getting booted for having “got into a jam with a tart.” The curmudgeonly Uncle Joe now lives in a “refuge for destitute old men” where he has converted to Islam of all things, and not surprisingly proves no help whatsoever.

Girlfriends come and go. The author’s writing career moves along. Various international journeys and part-time residences, both pre- and post-1984 – are recounted, including a poignant stay in New York in the 70s, as our author leads a rather nomadic life before settling down (kind of) and marrying a woman he met wearing a “plum-coloured rubber dress.”

The denouement consists of two striking scenarios: the one is the visit, years later, to the parking lot which used to be the tennis court where his mother died. He is led there by the woman with whom his mother was playing doubles. He wants to find the exact spot where she fell. Secondly, twenty years after the father’s death, the author seeks out his brother Ralph whom he has not seen in all that time. Ralph is still married to the same woman. He now lives in Singapore where Thompson flies for the reunion. The former encounter is eerie in its own way; the latter is nearly surreal, as the two estranged brothers walk through a dilapidated part of the city in a gray dusk where brutal questions are asked. And answered. Throughout it all, we feel the author’s compassion for everyone involved in this real-life drama - for all their faults, for all his. One is struck by the stark honestly that appears to have formed this memoir. I can’t imagine it was easy to write, though undoubtedly cathartic.

I do not wish to apply amateur psychology, but it is clear that the trauma of the death of his mother has formed the tone and direction of the author’s writing. Which is to say, it formed him. Had his parents lived, we would have a different writer. I wish his parents had lived – and the writer he would have become, I suspect, would dazzle us in another way. But they did not. And we have the Rupert Thompson we know – with one foot in the everyday world and one just beyond; with a tinge of mystery and a hint of danger in the most ordinary (and sometimes EXTRAordinary) exchanges; with an otherworldly feel at the borders of the everyday and a commonplace acceptance of the fantastical. He moves us to a place just under the surface, to a place very large and still . . . like a reservoir. A place he knows well. J.A.

© TBR 2010

These reviews may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission. Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization