TONY MACNABB

TONY MACNABB

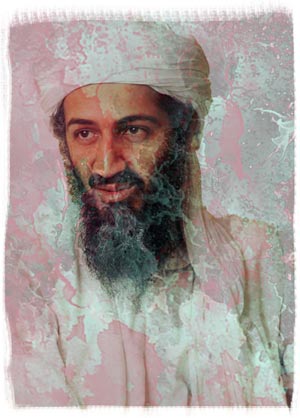

An Audience with Osama

The traffic was starting to build up. The driver fished a magnetic dome light from under the seat, attached it to the roof and blipped a siren.

“We’ve a bit of a way to go,” his companion said, a stocky man wearing a waxed jacket on this warm June day. “Would you like a paper?”

Dr. Rashid accepted a copy of the Daily Express. The story he had seen on the late night BBC bulletin was all over the front page. TERROR IN THEATRELAND, the headline blared in 60-point type over a grainy shot of a trade van rammed through the doors of the Queens Theatre, where the Prime Minister and his young family had been attending a performance of Oklahoma. The PM’s protection officers had arrested the driver at the scene. Apart from the fact that the driver was an Asian male, there were no further details, nor was it confirmed that the Ford Transit had been carrying an explosive device.

Dr. Rashid stared down at the image. The security forces had their man. He was undoubtedly known to them, and right now was being thoroughly questioned. It was just possible he had already been flown out of the country – but in that case why had Dr. Rashid’s presence been requested?

They turned off the M40 and onto the A355 towards Amersham. Waxed Jacket spoke briefly into a handset. Then they were turning down a single-track road between deep banks, trees arching overhead to form a tunnel. The driver slowed, swung the car wide, and made a sharp turn into a drive that wound through a chicane of rhododendrons to a security gate flanked by CCTV cameras. The gates swung open.

The house was a Victorian rectory in red brick. The ground floor windows were shuttered. The car drove past the porch and pulled up outside a Portacabin at the side of the building. From it, cables snaked across the gravel and vanished through a basement window.

The cabin was neon-lit, an office. A slim woman in her 40s stepped forward to greet him. “Good morning, Dr. Rashid. I’m Sarah Walsh. Thank you for coming in at this early hour.” She gestured sit down, and he lowered himself into a chair, his briefcase on his knee.

“First of all,” Sarah Walsh said, “I need to remind you that you have signed the Official Secrets Act,”

Dr. Rashid nodded. “Do I take it this is about last night’s attack?”

“In a way, yes.”

Dr. Rashid looked carefully back at her. Well tailored trouser suit. With her Home Counties accent and air of guarded amiability, she would not have seemed out of place in the Staff Common Room at the School of Oriental and African Studies, where he held a part-time teaching post. “I’m not sure I understand…” he began, but then the door opened and a grizzled man in his 50s came in. He went over to one of the desks, opened a drawer and started searching through the contents.

“This is Mike Farrell,” Sarah Walsh said.

“Asalaam alaykum,” Farrell said, still rifling.

“Wa alaykum salaam.” Farrell had a broad, weathered face, a shock of white hair and a hair lip. Or was that a scar? Blue denim shirt, brogues with stout leather soles.

Sarah Walsh went over to her laptop and worked the keyboard. She turned the machine round to face Dr. Rashid.

“Do you know him?”

Dr. Rashid peered at the screen. It showed a man sitting on a bunk in a windowless white room, staring at the floor. He wore a set of light blue overalls and gym shoes with no laces. He appeared to be chained to a bracket on the wall. The man glanced up at the camera and Dr. Rashid saw that he was overweight, bearded, youngish, and white. There seemed to be a bruise on one side of his face. Sarah Walsh pressed a key, and the image changed to a mug-shot of the same man, minus the bruise, staring into the lens with a glazed truculence Dr. Rashid had seen before on other faces, most of them brown or black.

“I’m afraid not,” he said.

“Really?” Farrell had found a buff folder containing a thick sheaf of paperwork, which he let fall on the desk. “He was a student of yours back in 2002. One Alan Knight. Now calls himself Omar al-Siddiqui.”

Dr. Rashid remembered him now. He had dropped out of his undergraduate course after a year. Dr. Rashid cleared his throat. “I was under the impression that our jihadi was Asian.”

“The papers get a lot of things wrong.”

“Knight has so far resisted the interrogation options available to us,” Sarah Walsh said. “We hoped that you would be able to bring your expertise to bear.”

“How, exactly?”

“The bad cops have failed to obtain the info we want,” Farrell said. “It’s good cop time.”

“I am not a cop,” Dr. Rashid said. “Most of my work has been conducted for Home Office Committees. This isn’t my area.”

Sarah Walsh smiled. “Believe me, we would not have called you in unless we thought you might be helpful. Your usual fee will of course apply.”

Dr. Rashid took a deep breath. “What exactly do you want me to do?”

“We want you to engage him in dialogue. Assess his state of mind. Trawl for anxieties.”

“I would imagine that he has a few of those right now.” Dr. Rashid looked from face to face. “Look, I would appreciate a more thorough briefing.”

“We’d rather you went in there and had a chat with him.”

“And if you don’t get what you want?”

“We review our options.”

Dr. Rashid glanced at his watch. It was now 8.50 a.m., some ten hours after the attack. Whatever other qualities Alan Knight might or might not possess, he was resilient.

Dr. Rashid got to his feet. “I will do what I can.”

“Good. But I must ask you to leave your briefcase here.“

Farrell escorted Dr. Rashid through the back door of the rectory and down a tiled service corridor that echoed with the clump of his brogues. Two large men wearing overalls and high-laced boots were sitting drinking tea at a pine table in what had once been a pantry. There was a butler’s bell box on the wall, rusty wires trailing from it, and an old ceramic sink with brass taps. On the table were tea cups and a large box of latex gloves. Farrell went inside and spoke to the two men for a moment, then they followed him out into the corridor.

“All right, lads,” Farrell said. Then he turned and walked away.

Dr. Rashid followed the lads to the end of the service corridor and down a flight of stairs leading to the basement. “Mind the cables, sir,” one of them told him.

The smell of fresh paint hung in the air as they entered a subterranean corridor, this one lined with grey metal doors. The strip lighting was very bright. One of the interrogators pulled back a metal slide and peered inside the cell. Then he turned to Dr. Rashid. “He can’t reach you unless you get close, sir. When you’re done, just bang on the door. We’ll be outside.”

Alan Knight looked up as the cell door clunked closed, and for a second Dr. Rashid saw surprise. Then Knight’s features relaxed and he stared back, eyes blank and shiny in his doughy face. Dr. Rashid could now see he had an angry abrasion on his cheekbone. His left wrist was manacled to the wall.

“Asalaam alaykum brother,” Dr. Rashid said. “I have been asked to come and have a word with you.”

“That does not surprise me,” Alan Knight said. His voice was hoarse, as though exhausted by shouting.

“Oh? Why is that?”

“Because they think that someone like you can wheedle information faster than they can beat it out of me.”

Two chairs were ranged along the wall opposite Alan Knight’s bunk. Dr. Rashid sat down on one of them. “I’m not sure that applies. Our acquaintance was brief. I hardly know you.”

Alan Knight gave a rusty laugh. “But I know you. I’ve seen you on TV. The champion of interfaith dialogue.”

“You disapprove of that, I take it.”

“The Zionists and Crusaders are mounting the greatest assault on Islam in a thousand years, and you spout Sufi poetry and preach appeasement.”

“I don’t preach, Omar, I advise…”

“In the name of a culture that reduces life to a meaningless exercise in futility?”

Dr. Rashid suppressed a groan. Whatever their education, these young men talked in the rhetoricof Wahhabi imams, just as Marxist blowhards once parroted Lenin or Trotsky.

“Islam is the light by which God discloses Himself to man, and to all of creation,” Dr. Rashid said. “It cannot be destroyed.”

“That does not stop infidels slaughtering our brothers and sisters from Chechnya to Afghanistan.” Alan Knight ‘s nostrils flared. “‘It is written, ‘Take not the Jews and Christians as allies, for they are but allies to one another. And if any amongst you takes them as allies, then surely he is one of them.’”

“I’m sure we could sit here all day long trading verses from the Holy Qur’an, but we would get nowhere. Tell me, brother…”

“You’re not my brother.”

“Tell me then, Omar, about how you came to the Faith.”

“If you think I am going to compromise my brothers and sisters, you have another thing coming.”

“I merely wished to find out what brought you to the Dar al-Islam,” Dr. Rashid said.

“I have been to your house. I have drunk your sherry, met your kuffar wife and her dog. So don’t talk to me of the House of Islam.”

Dr. Rashid’s wife Rosemary owned a Norfolk terrier. He slept on their bed. One of Dr. Rashid’s reliable pleasures was to walk him on Parliament Hill at weekends.

“After all these years you remember Digby,” Dr. Rashid said. “I’m touched. Even if you have forgotten our tutorials...”

“An angel will not enter a house where a dog is kept.”

“I thought I missed the sound of beating wings.”

“Don’t try to be cute.” Alan Knight coughed and wiped his mouth on the sleeve of his overall. “You’re a stooge and a white arse kisser. And in your soul, you know it.”

Dr. Rashid regarded with distaste this idiot who had made a God of his own anger and was intent on serving it. It was on the tip of his tongue to say as much, but he checked himself.

“It is interesting, if ironic, that you should call me a white arse kisser,” he said. “In my youth, I was a Communist. In the Seventies, many liberation movements in Muslim lands fought under the red flag, but one could criticise Communism without being labelled a racist.”

Alan Knight sneered. “You speak of Communism and Islam in the same breath. You are not a Muslim. You are an agent of Satan.”

“But my duties are purely ceremonial.” Dr. Rashid smiled. Alan Knight looked blankly back at him.

“An old joke,” Dr. Rashid said. “Do you mind if I smoke?”

“Yes.”

Dr. Rashid dug a packet of Rothmans from his jacket pocket and lit one. “Let me ask you something. What makes you think that you have not succeeded in your mission of martyrdom?”

Alan Knight’s red-rimmed eyes blinked rapidly.

“For all you know, you succeeded,” Dr. Rashid told him, “but you miscalculated badly and now you are in hell. And I am indeed an agent of Satan, sent to torment you.”

“Screw you, Rashid.”

Dr. Rashid brushed some ash from his shirt front. “As I mentioned before, I was once a Communist. I found dialectical materialism irrefutable. I too detested lackeys and backsliders, the ‘apostates’ of my creed…”

“You’re boring me, Rashid....”

Dr. Rashid held up a hand, and to his surprise, Alan Knight fell silent. “Then my father died. I flew back to Bengal to bury him.” Dr. Rashid studied the tip of his cigarette. “As the earth fell on his shroud, political argument seemed utterly irrelevant. I understood that all of time exists as a single moment in the mind of God, an outpouring of ineffable light. I suppose you could call it a vision.”

“You suppose?” Alan Knight laughed, and the saliva rattled in his throat.

Dr. Rashid said nothing for a moment. Alan Knight turned away and stared at the wall.

“My father named me Joseph,” Dr. Rashid said, “after Josef Dzhugashvili,” also known as Stalin. Now I call myself Yusuf.”

Alan Knight said nothing. He seemed to have gone into a trance, picking fitfully at the cuticle on his thumb.

Dr. Rashid allowed himself to go into tutorial mode. “It was the singular election of the Prophet, Peace be upon Him,” he said, “to transmit to mankind a way of transformation...”

“Islam is the way of life ordained by God for mankind,” Alan Knight barked, the links of his chain rattling as he gestured. “Life is political. You seem to have forgotten that in your wanderings.”

“And indeed the Prophet was a political man,” Dr. Rashid persisted, “uniting the tribes of Arabia that had dwelt in jahiliyyah. But he was able to do so because he received the keys of the Unseen. I doubt he would approve of al-Quaeda, who have no political agenda beyond hammering unbelievers in the hope that the umma will somehow unite and organise itself into a Utopia.”

Alan Knight said nothing. A muscle in his jaw jumped.

“You are consenting to be defined by your enemies,” Dr. Rashid said. “Instead of Islam transforming you, you are transforming Islam. You plunder the Noble Qur’an for pretexts for violence, just as the Crusaders once did with the Bible.”

There was another silence. Dr. Rashid imagined Walsh and Farrell hunched intently over their screens, trying to guess which way this was going to go.

“Tell me brother,” he said to Alan Knight, “what is the greatest jihad?”

“To defeat the enemies of the Faith in battle.”

“And who are the greatest enemies of the faith?” Dr. Rashid leaned forward, his elbows on his knees. “Mortal men who distort the teachings of God’s Messenger. The greatest jihad is fought in the human heart, for only the heart can perceive God.”

Alan spat pinkish saliva on the floor. “You have been hanging around Christians and pestering Jews too long.”

“I have said what I believe to be true, and you respond with abuse,” Dr. Rashid said. “I really don’t know what I can do for you.”

“Nothing. There is no God but God, and he knows the purity of my intention.”

“You didn’t kill anyone, Omar. You were a failed student, and now you are a failed terrorist. You will be in prison for a long time. One day you will be released, and you will have nothing.”

“You are the one who has nothing. You are old. You are impotent. And you will burn in Hell.”

“There’s still your failure, though, isn’t there? I’d think about that, if I were you.”

“Yes, I failed. But do you think you can stop us? You don’t need a billion dollar missile programme to deliver a nuclear bomb. All you need is a van and someone willing to drive it.”

Dr. Rashid crushed out his cigarette and got to his feet. His chest hurt, he felt dizzy and he badly needed to urinate. “I think our little chat has reached its conclusion.” He knocked on the cell door.

“Goodbye, Dr. Rashid,” Alan Knight said. “I doubt we’ll meet again.”

The two interrogators escorted Dr. Rashid down the corridor and up the stairs that led back to the world.

“Excuse me,” Dr. Rashid said as they made for the service entrance, “do you have a lavatory?”

“Just over here, sir.”

The interrogator opened a door into a large tiled washroom. Two young women were at the mirror, applying make-up. The first thing Dr. Rashid noticed was they were both wearing identical parkas. Their legs were bare, and they were both wearing sequined silver slippers. Their eyes were ringed with kohl, like silent movie stars. A heavy perfume hung in the air, sweet and cloying. One half turned to look at him, an alarmed expression on her face, and Dr. Rashid saw that she was naked under her parka. Then the interrogator was closing the door again. The whole episode had lasted perhaps a second.

“Sorry about that,” he told Dr. Rashid, “they’ve a toilet outside.”

Back in the Portacabin, his bladder emptied, Dr. Rashid drank thirstily from a bottle of chilled water.

“Well?” Farrell said. “What do you think of our Mr. Knight?”

“Someone for whom violence promises redemption,” Dr. Rashid said. “He’s been brainwashed, he talks in slogans. He’s probably quoting his martyrdom video. Incidentally, some things he said were almost direct quotes from Osama bin Laden.”

Sarah Walsh glanced at Farrell. “And?”

“When he drove that van through the doors of the theatre, he believed he was moments from paradise. Now, here he is.”

“Would you say he is hopeful that he will be received into Paradise?” Sarah Walsh said.

“I would say he was counting on it,” Dr. Rashid said sourly.

Sarah Walsh said, “Knight isn’t the bomb maker. He knows it’s not his fault the device didn’t go off.” She opened the fridge in the corner and helped herself to a bottle of water. “But he knows he’s failed. He is between worlds, so to speak.”

“Purgatory,” Farrell said. He fished a handkerchief out of his sleeve and blew his nose loudly.

“You could describe his subjective mental state that way,” Dr. Rashid said. “There is, however, no purgatory in Islam.”

“Then he will be in for a surprise.”

“You mean he is going to die?”

“In a manner of speaking.”

“One does not die in a manner of speaking.”

“Carl Jung would disagree,” Sarah Walsh said. “Death and rebirth are the central themes of his psychology, and of course of a great deal of mythic narrative, which is its foundation.”

For one mad moment Dr. Rashid fancied he was indeed back in the SOAS Common Room, conversing with an attractive academic colleague. “I fail to see what Carl Jung has to do with this,” he said.

“We feel the answer to our problem with Knight could lie in enacting a form of psychodrama,” Sarah Walsh said.

“You mean you are going stage an encounter in the afterlife?” Dr. Rashid looked from one to the other. “I do hope this is a joke.”

“The bomb in that truck wasn’t made of hairdressing products, “ Farrell said, “ they used military grade explosives. If it had detonated, half of Soho would be smoking rubble. There’s almost certainly more stashed away somewhere, and next time they may not louse it up. So, no joke. After we catch these bastards, we can have a laugh together, if you like.”

Dr. Rashid found a tissue in his pocket and dabbed at his mouth. “And in this psychodrama, who will be impersonating God, if I may ask?”

“That is not quite what we had in mind,” Sarah Walsh said. “As you rightly observe, this man quotes Bin Laden. In fact, he idolises him. We are going to arrange an audience with the Sheikh.”

“There is a problem. Bin Laden is alive.”

“For the purposes of our scenario, he was killed by an American drone in 2008.” Farrell eyed him over his glasses and Dr. Rashid felt rage coming off him like sweat off a hard-ridden horse.

Dr. Rashid cleared his throat. “And how are you going to achieve this effect?”

“You can leave the details of the mise-en-scène to us. “ Farrell opened the buff file lying on his desk, took out a magazine and held it up so that Dr. Rashid could see the title The Journal of Islamic Studies. “On page 36, we have a long and authoritative article by your good self, Osama bin Laden and the Arab Rhetorical Tradition. You are going to help us get the words right.”

“You want me to be the dialogue coach in this pageant of yours. That is the real reason you brought me here.” Dr. Rashid felt a ballooning sensation in the pit of his stomach. Merciful God, the women in the washroom were part of the cast of this hellish charade. They were houris, the handmaidens of martyred warriors.

“You are going to stage a mock execution,” Dr. Rashid heard himself say, “or give him drugs. Or both. And you are going to play with his mind until he gives you the information you want.”

“You’re getting the hang of it,” Farrell said.

“That is obscene.”

“Not as obscene as fifteen hundred people dead under the wreckage of a London landmark.”

“You yourself suggested much the same thing, ” Sarah Walsh said. She worked the keyboard of her laptop, and Dr. Rashid heard his own cheerful voice say: For all you know, you succeeded. But you miscalculated badly and now you are in hell. And I am indeed an agent of Satan, sent to torment you.

Dr. Rashid, who had risen to his feet, sat down again abruptly. For a second he thought he might faint.

“Are you all right?” Sarah Walsh asked. “Have some more water. Still or sparkling?”

Dr. Rashid shook his head.

Sarah Walsh pulled a chair from behind her desk and came and sat close to him. “Knight does not speak much Arabic, but he has read Bin Laden’s messages in translation. We want you to brief our man on his vocabulary, the grammatical tropes he uses, the cadences of his speech. His favourite passages in the Qur’an and the haditha.”

“I won’t do this,” Dr. Rashid said. “This is beyond all reason.”

Sarah Walsh glanced across at Farrell, who was leafing through the buff file.

“I see that you are not a British Citizen, have been granted right of abode in this country,” Farrell said. “We might have to look into that.”

For a long moment, Dr. Rashid sat motionless in his chair. He had no doubt that if Knight held out, as he had done for almost twelve hours, he would be despatched somewhere torturers could still earn an honest day’s pay. Morocco, for instance. Or Russia. So what was morally preferable? To violate Knight’s body, or tinker with his corrupted mind?

“Very well,” Dr. Rashid said.

Farrell gave Sarah Walsh a nod. She picked up a phone and spoke briefly into it. There was a long silence. Then came a knock on the door and a tall man stepped into the Portacabin, so tall he had to duck his head in the doorway. He wore chinos, a denim shirt and rubber clogs and a towel draped around his neck, but the grave, bearded face that looked back at Dr. Rashid was that of Osama bin Laden. He carried a spiral bound notebook, and a small voice recorder. Farrell fetched a folding chair and placed it opposite Dr. Rashid. Osama unfolded his notebook. He took a ballpoint pen from his shirt pocket and placed the voice recorder on the floor between them.

Dr. Rashid took a deep breath. Under the harsh strip lighting, he could see the stage makeup on Osama’s face.

“There are five types of public discourse in the Islamic world,” Dr. Rashid said, “the juridical decree, the lecture, the epistle, the admonition and the declaration. In his public statements, Osama bin Laden uses all five. I would like to review these for you. ”

It was almost midnight by the time the Vauxhall Vectra brought Dr. Rashid back to his house in Cricklewood. The driver held the door open for him, and Dr. Rashid levered himself out of the back seat. Waxed Jacket reached inside the car and handed him his briefcase. “Ms. Walsh says, send your invoice to the usual place, and she’ll see that it’s paid.”

Dr. Rashid unlocked his front door and stepped into the darkened hallway, laying his briefcase on the hall table. His back and knees ached. His airways felt raw and inflamed. The events of the whole nightmarish day churned in his mind in a jumbled montage as he shuffled into the kitchen and subsided into a chair. There was a note from Rosemary on the table. Lamb stew in fridge x. The thought of food repelled him. He got to his feet and opened the kitchen cupboard where Rosemary kept a bottle of brandy. The last time it had been touched was when her sister had gone into hospital three years ago. Dr. Rashid took down the bottle and poured himself a glass. It had been a long time since he had taken a drink, and he instantly felt light headed. Was that why people drank so much, because they could not bear the shame of their lives? Perhaps his former pupil Omar al-Siddiqui was right. He was old and impotent. All he could do was spout conciliatory waffle.

Rosemary was asleep under the duvet, her breathing slow and regular, Digby was curled up beside her. Dr. Rashid laid a hand on the swell of her hip, but then decided not to wake her. Instead, he sat there stroking Digby’s wiry fur for a while. What would they do to Omar? Would they stage a mock execution? And while he was unconscious, drug him? What drug? A hallucinogen perhaps. LSD? Given the scenario they had in mind, it would be an appropriate choice. During his years as a student at Kings College, Joseph Rashid had taken LSD one weekend, at a cottage in Wales. In truth, it had been the illuminations of that weekend, and not his father’s funeral, that had been the start of his journey into Sufism.

Dr. Rashid buried his head in his hands. Alan Knight, failed student turned Salafist zealot, would soon awaken to be confronted by his hero, Osama bin Laden, and two naked houris. Alan Knight would give Osama whatever he asked for, his soul if necessary.

Dr. Rashid prised off his shoes, and struggled out of his trousers. He pulled back his own duvet and stretched out under it with an old man’s audible sigh of relief and closed his eyes. He felt a huge weariness at the mad enterprise Alan Knight had involved himself in, the madness of the spooks’ plan, the heartfelt and industrious madness of Bush and Blair. Was it true that only the dead know the end of war?

He turned his head and peered at the bedside clock, glowing softly beside him. Half-past midnight. Soon he would sleep. Let me not dream, Dr. Rashid said in his heart, not quite sober. In dreams, one mind might flow into another, and in a rectory in the English countryside, an eyeblink away, his former student would have begun his audience with Osama bin Laden.

© Tony Macnabb 2010

This story may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission. Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization

Tony Macnabb is a writer, script consultant and translator. He has worked in both feature films and TV, for the MEDIA programme of the EU and as a tutor on PILOTS workshops. He has been a regular tutor at the National Film and Television School Short Course Unit, and is co-author with Tony Bicât of Creative Screenwriting (Crowood Press 2002) ISBN 1-86-126-525-5.

Tony Macnabb is a writer, script consultant and translator. He has worked in both feature films and TV, for the MEDIA programme of the EU and as a tutor on PILOTS workshops. He has been a regular tutor at the National Film and Television School Short Course Unit, and is co-author with Tony Bicât of Creative Screenwriting (Crowood Press 2002) ISBN 1-86-126-525-5.

His crime thriller The Price was published in August 2008 by Kings Hart Books ISBN 978-1-906154-080

More information and CV on www.tonymacnabb.info

Contact the author