The Power of Predictability

M.G Smout

Original is not an achievable goal in novel-writing.

So just throw that word out the window right now. What is achievable is fresh…

Our job, as writers, is to tell a new version of a familiar story that we already know readers are hardwired to respond to.

Save The Cat! Writes A Novel by Jessica Brody.

Picture this: We are introduced to a character who is not necessarily a bad person but has high standards (work, family background) which they seek to achieve or maintain. This person takes an instant dislike to our hero and animosity grows. However, in trying to maintain their standards something for them goes horribly pear-shaped. Somehow, from somewhere deep down, we have a pretty good idea that Hero and Character will now form an allegiance. Add one other factor: what ever went pear-shaped means disgrace for the family and a ruined career. Almost instantly we know that this character will die saving the hero’s life. How, or why, do we know or presume this? It is simply because this self-sacrifice is a cliché that appears in countless westerns, war and disaster films and books; it is therefore predictable and as such one would think no writer in the 21st century would touch it with a barge pole. Think again. As soon as Lt Commander Mark Prentice appeared in episode 1 of the BBC’s 2021 six-part Vigil I knew his fate. It is blatant, no twists. Or was the lack of twist the twist itself? When Prentice met his end I was in two minds; a fist pumping ‘I got it smack on’, contrasted with amazement that the BBC would go with such a corny chestnut.

One would think predictability in a story is a negative element to be avoided, but the predictable is a curious animal. We are creatures of habit and, to a certain extent, we actually like predictability in our lives. Without it there could never be such a delightful thing as a surprise, and it is the desire for a hassle-free continuity that makes ‘May you live in interesting times’ a curse. In a story, or film, we like that ability to see ahead and blurt out the possibility about to unfurl, such as the classic; Oh, they had sex, so they’ll be the first to die; the obvious: Bet the school nerd ends up with the school cutie; and of course the Just know the baddie will die in the shark tank we glimpsed in the beginning, etc. In a romantic novel, or a rom-com, predictability is extremely high; we know it will be along the lines of: two meet-fall in love-shit happens-split up-meet up again-happy ending. Therefore, depending on genre, we can pretty much predict parts of, as well as the conclusion of, many films and books, yet we still watch, or read, because it is the winding journey to the known end that interests, not so much the actual foregone conclusion. But doesn’t any type of predictability indicate lazy, clichéd writing?

A storyteller creates for an audience, not just for themselves, and will therefore use something universal, something familiar, even clichéd, to draw in their audience, and once there, once in the palm of their hands, comes the surprise, the angle that breaks away from the known, predictable path. Be it the music we listen to, the films we watch or the books we read, there is a comfort when they follow certain patterns and ‘shapes’ because we can sit back and be entertained knowing our brains are not going to be over-taxed. A shift away from the norm is totally acceptable, in fact wanted, as our entertainment does indeed often need a challenge; it becomes fresh, a ‘twist’. A song with no chorus is seen as original, a film whose story is told backwards becomes fun and the hero getting killed is fine. However, take it to the extreme and throw away the patterns, chuck out the comfort of predictability, then we get discordant music, pondering bleak films and dense literature. There are many who love this, who can thrive on the randomness and lack of structure, but the majority will want a quick return to those easily understood patterns and shapes.

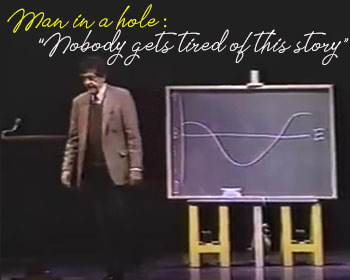

In his lecture ‘The Shape of Stories’ (see video clip) Kurt Vonnegut says of the shape that is a simple curved dip in a straight line that ‘nobody gets tired of this story’. He calls it ‘the man in the hole’ which succinctly sums up the basic plot of a protagonist’s normal life thrown into chaos, into the ‘hole’, before normality returns as the ‘hole’, whatever it is, is conquered. It is how the protagonist gets into and out of the hole that is the actual meat of the story. It could be a horror story, rom-com, war film, anything, even a joke. We have seen and read this ‘shape’ countless times under various guises and, as the man says, we never tire of it. We like the predictability. And that basic dip can be played with: flip it and it could be a person down on their luck, which changes to good fortune which then goes negative, possibly because the protagonist is a badass or wishes it or, as in the story of Cinderella, returns to good fortune. Horror films will often add a line right at the end that goes straight back into the hole: the hand suddenly shooting out of a grave, a rat running off with a bit of the monster everyone thinks dead. It is important here to stress two things. Firstly, these shapes could apply to the story as a whole, but more likely to the main protagonist, with other characters having different ‘arcs’; for example, Cinderella’s step-mum and sisters don’t come back out of the hole. Secondly, Vonnegut’s idea was heavily frowned upon by academia because, according to him, ‘it was so simple and looked like too much fun’.

Storytellers seem to have endless possibilities based around these few classic ‘shapes’ but seem reluctant to go beyond them. Why don’t they branch out, tell another, different story? There must be hundreds of others out there?

The truth is it seems there are not hundreds of non-plundered plot lines waiting in the wings and the options are limited. Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations written in 1895, does what it says on the tin and lists 36 typical story/plot concepts/situations, but since then, regardless of world wars, pandemics, space travel and so on, nothing new has ever been added. Nothing, nada, zilch, zero. In fact, in the 120 years since it seems the opposite is happening with the number being radically reduced and we now do not have 36 situations after all. Christopher Booker thinks there are only seven plots and then it got worse when computers, fed and overdosed on literature, decided it was just six. These six are worth listing; note the ‘shapes’ in parentheses.

- Rags to riches (an arc following a rise in happiness)

- Tragedy or riches to rags (an arc following a fall in happiness)

- Man in a hole (fall-rise)

- Icarus (rise-fall)

- Cinderella (rise-fall-rise)

- Oedipus (fall-rise-fall)

I think, in a nod to Kafka, we need to add:

- Cockroach (fall-mega fall)

For those intrigued by the number of plot lines, dramatic situations and emotional arcs and what they are, then a concise article ‘Are there 3, 5, 7, 9 or 36 Different Plot Types? [The Definitive Answer]’ by Emma Bullen may be of interest.

Therefore, logically, the 50 hours of Game of Thrones or the 70 of The Walking Dead must have each covered some, or all, of those situations. As too The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, Sons of Anarchy, Vikings, and on it goes for thousands of viewing and reading hours. And no matter what, be it sword, sorcery, gangsters or drugs, the themes dealt with inside each storyline would also be familiar: alliances made and broken, treachery, betrayal, revenge, sibling rivalry, the powerful woman and so on. Yes, Jessica Brody is right—nothing is, or can be, 100% original; we are familiar with all the storylines, we have been told the same story many, many times yet somehow we do not notice, or care, that we are being fed the same old, same old.

With these ever-shrinking plot lines, give a thought for the authors who work in even more restrictive markets like romance where, as mentioned, predictability is high and where that required happy, uplifting ending instantly reduces the story and leads protagonist’s plot lines to being just three of the six. Romance publisher Mills and Boon ties the author’s hands even more and demands that the two main characters meet in chapter two and not have had a previous love life. I asked best-selling romance author Veronica Henry, who apart from numerous books has worked in TV, about the problems of writing within a restrictive framework. ‘The key for me is character. Yes, there are a limited number of plots and story structures we tend to conform to—but who we choose to tell those stories through is what keeps it fresh’ (see full interview).

So, apart from the character, how else do writers manage to spin the same yarn and keep it fresh without boring us rigid?

Because that is their job and nine times out of ten they are bloody brilliant at pulling the wool over our eyes. They have their ways: they distort, disguise, mix, meld, change chronological sequences, and of course, play with our need for predictability to lure us in then spin us out with a twist or three. (I go into a little more detail on this below). Writers are, no, have to be, a devious breed. We the reader, the viewer, are led like sheep by a clever shepherd (the sheep analogy will end soon!) because not only are we following a familiar path, but we are also being told, especially in many films, the exact places to eat and what to eat and swallow. In a typical ‘man in a hole’ film we know by the 5-minute mark something will be shown (that shark tank!) or said that has relevance later. We know well before the 15-minute mark what the catalyst is that will trigger the film away from the initial set-up. Before the halfway mark there will be some sort of nice bit with everyone happy then just after halfway it all turns to manure. It seems like it is in our blood; thousands of years of storytelling round the fire, round the radio, in front of the TV, has indeed hardwired us to wanting predictability in order to help us not only absorb but tell our own stories in a manner others will instantly latch on to, to understand and respond to.

I know this from my own experience. I had an idea for a film and wrote down a very vague plot line, basically a simple sequence of events. I had no clue what to do next but was pointed to several books, one of which was Blake Snyder’s Save The Cat! (2005). He had observed that so many films had a definite pattern and that key events, 15 in all, pretty much happened at set times. He wrote them up, called it his ‘beat sheet’. I looked at my effort and saw that, untrained and unaware as I was, I had not only the 15 beats, but they were in the same order. My own subconscious had shifted through my viewing and reading experiences, going back to god knows when, to help instruct the manner in which the story should be played out. It would appear storytelling really is bred within us.

And that predictability can be enhanced and manipulated even more. A minute in a film is more or less equal to a page of film script, so when Snyder lists his 15 beats, he also adds the page number as it would/should appear in the script. The fact that Save The Cat! has become so revered in the industry means it has become a template; it has predictability practically timed to the second, to the very beat of our hearts and souls. And a template is far more useful than a guide. I not only had my beats but now I can fine tune the script. If my ‘catalyst’ is not happening around page 12, then I need to edit and trim what happens before. It may be scriptwriting by numbers but for a rank amateur like myself it is a damn good place to start; it is as if somebody is holding your hand. In reality I know, because there is a lot of music in my intended film, that those page numbers are never going to match the timing and I know that no way would my script end up on screen exactly the way I wrote it. There are, of course, numerous advice books on screenwriting, many obviously damning Snyder for his simplistic, formulaic approach, but it is a book that should be given some respect for a method that helps rookies get results. Jessica Brody ‘borrowed’ this formula and came up with her take titled Save The Cat! Writes a Novel, which, obviously, also has detractors.

Let’s play at being a storyteller. I should point out that this might read as being ‘film’ heavy, but remember, long before the director or actors are involved, a film starts life as a written format.

Purely by using our own hardwired familiarity with the world of fiction, and understanding that the end user often needs the comfort food of predictability, we can—and forgive me but this needs to be extremely generalised and simplistic—do something like this:

In a raw basic state, a story should have a definable genre, be it thriller, rom-com, mystery, drama etc. Next it must have a beginning and a conclusion (which in something like Memento can be reversed). It is very trendy, and often annoying, to have a film start then have a second start, as in; ‘Ten days/months/years earlier’. This device is, of course, a way of distorting the predictable timeline. There can be several ‘middles’ depending on different characters, and these can appear at the start followed by that annoying ‘ten years earlier’. Whatever, the main character must usually have a learning curve, a redemption, something; i.e., they are changed in some way at the end. And there must be, has to be, conflict. No conflict, no story.

Let’s say we have a happily married couple. If we change the genre, we automatically change the obvious possibilities. If a thriller, there is a high probability one of them is murdered and the other seeks revenge. If horror, one tragically dies and, maybe, returns as a ghost or the survivor seeks to reverse the other’s fate with devastating consequences. As a drama, one dies and the other must overcome the loss and start a new life. Elements of the latter can, of course, be used in the others. For our case, we want a light, domestic drama of about 100 minutes. Happily married possibly implies no affair, so 100% something shifts—it has to otherwise there is no story—changing their domestic bliss. For example, one must lose their job and the couple has to downsize and move. Add a child, so conflict over the parents’ decision to move; new school: 100% problems, 80% a falling out will follow. Add two children: one child (90%) will be the oddball, sibling rivalry, with 100% conflict and a falling out with one or both parents. Then 100% something happens: in a family—remember it is a light drama—there is a 100% probability that any conflict between parents and child is resolved.

With predictability this high, writers at the studios—that’s us in this role-play—have to come up with a way of making this old chestnut with its overworked, hackneyed storylines seemingly new and fresh. Some of the above template actually tells the opening sequence to Disney’s Inside Out, which then goes off on another tangent, but returns for the ending. We have to cleverly dupe the audience into believing they are watching original material. And this can be done quite simply. A perfect example is the recent Superman and Lois which follows the above template story-wise, but, as it is a 15-part series, not timewise. The viewer is cleverly distracted from the oh-so-obvious-it-hurts plot lines by the simple twist of having Clark Kent (AKA Superman) as the father figure suffering the sudden downward shift in his happy domestic bliss. We see Superman trying to be a dad and doing oh-so-funny things like arriving at the kids’ school far too quickly and trying to hide his identity from them—they have never seen him at home without his glasses? Really? Apart from being a little cheesy, it is better than some of the cinema releases. Another well disguised, in fact at first a brilliantly well disguised, plot is Wandavision, which—spoiler alert— in its basic plot follows the idea above about a partner recovering from the loss of a loved one.

And, in a nutshell, that is all that is happening. As with Superman and Lois, a writer doesn’t have to break sweat and can merely use tried and tested plots with only some sort of distraction disguising it. Take a rather mundane, over-told horror movie plot of a group of people finding a house and accidentally waking a monster which then starts killing them off with a female being the one that fights back. This is not going to get many backers and will be yawned out the room. Shove the same story into space, call it ‘Alien’ and for added freshness have the female not scream and we have a blockbuster.

Possibly thanks to Alien, sci-fi, once a clever way of parodying, satirising or mocking our world, has become an easy way of deflecting attention away from a familiar storyline. This helps to explain why so much out there is now sci-fi, fantasy or superhero. Another deflection, making the same old material look different is a same sex relationship, which at the moment is usually girl on girl (The 100, Cowboy Bebop, Fort Salem). I presume lesbianism has been deemed safer for the general public’s appetite to handle, so thank the gods for Sex Education (itself telling a reasonably conventional school/bully/nerd story), which covers all grounds.

The most blatant deflection away from ‘same old story’ has to come from Marvel (AKA Disney) and the Marvel Universe. The desire to create a world where all the superheroes’ lives and realities intermix means our attention is taken away from the story by trying to see how this particular film will link in with Iron Man, Thor, Guardians of the Galaxy and Jessica Jones. The House of Mouse wasn’t going to have a drunk like Jones on their books, so she got dumped making connections a wee bit easier. Even so, a lot of people’s attention is successfully diverted from the usual lose/regain powers in a superhero story as they look for holes in the multiverse. And, as there are quite a few, Marvel came up with ‘What if…’ which was nothing more than moving a few facts around but by doing so really muddies the water—Captain America is a British woman, etc., meaning that Captain America could, at any point, be an Indian woman, an Australian kangaroo, an African dung beetle, whatever Marvel wants it to be. Viewers dizzy with confusion focus on the conceit and not the over-told story, clever in some respects, but let’s be honest here, it is also wonderfully lazy. However, not as clever as taking a pretty obvious high-school story mixed with a superhero-origin story then having the 11-year-old Hit Girl endlessly use ‘fuck’, and even call the baddies ‘cunts’, before graphically hacking them to death in a bloodbath. With jaw on floor the viewer completely forgets they are watching the usual predictable school-kid-nerds-bully tale. Kick Ass 1 and 2 blow tame, lame, blood and expletive free Marvel out of the, er… universe.

The most blatant deflection away from ‘same old story’ has to come from Marvel (AKA Disney) and the Marvel Universe. The desire to create a world where all the superheroes’ lives and realities intermix means our attention is taken away from the story by trying to see how this particular film will link in with Iron Man, Thor, Guardians of the Galaxy and Jessica Jones. The House of Mouse wasn’t going to have a drunk like Jones on their books, so she got dumped making connections a wee bit easier. Even so, a lot of people’s attention is successfully diverted from the usual lose/regain powers in a superhero story as they look for holes in the multiverse. And, as there are quite a few, Marvel came up with ‘What if…’ which was nothing more than moving a few facts around but by doing so really muddies the water—Captain America is a British woman, etc., meaning that Captain America could, at any point, be an Indian woman, an Australian kangaroo, an African dung beetle, whatever Marvel wants it to be. Viewers dizzy with confusion focus on the conceit and not the over-told story, clever in some respects, but let’s be honest here, it is also wonderfully lazy. However, not as clever as taking a pretty obvious high-school story mixed with a superhero-origin story then having the 11-year-old Hit Girl endlessly use ‘fuck’, and even call the baddies ‘cunts’, before graphically hacking them to death in a bloodbath. With jaw on floor the viewer completely forgets they are watching the usual predictable school-kid-nerds-bully tale. Kick Ass 1 and 2 blow tame, lame, blood and expletive free Marvel out of the, er… universe.

All this deflecting and repositioning works but is rather simplistic and can often fail. Kick Ass only worked because it was so gloriously over the top. We want a certain amount of predictability. Some markets demand it, so often the poor author/scriptwriter has nothing else to work with but predictability and therefore must use their storytelling skills to the max to weave it effectively. Veronica Henry, in her latest book, has taken the ‘reposition’ approach by moving on from the conventional ‘uplifting’ romance between bright, young things to a story of a sixty-something-year-old woman. ‘I wanted to write a book about an older woman having agency and dynamism and still being hot and entrepreneurial. It’s also about a mother, daughter and granddaughter pulling together to realise a joint dream. And the effect that has on the local community. They change lives because they’ve dared to change their own.’ The author said ‘character is key’— but we are also aware that Henry is remaining within her market and, as an uplifting, escapist novel, we know there is going to be a catalyst and conflict while the ending will be happy.

In episode 8 series 4 (2022) of the afternoon UK TV show Shakespeare and Hathaway (a detective agency set in Stratford-upon-Avon if you were wondering), the writers took the viewers hardwired preconceptions of its typical fare and spun them on its head. Among a tray of red herrings, the usual murder never happened and the young model marrying the older man who had just won millions on the lottery was not a gold-digger but actually in love. What is extraordinary about this is that it seemed fresh, almost original, and yet, on reflection, nothing happened; the story was about people being sort of normal with some misconceptions thrown  in. A totally new viewer to the series would have been baffled but regular viewers must have smiled, knowing they had been well and truly played.

in. A totally new viewer to the series would have been baffled but regular viewers must have smiled, knowing they had been well and truly played.

Another fine example of toying with the predictable comes from Disney. In children’s stories the baddies are obvious, from the very moment they are first seen. However, in Frozen those preconceptions were shattered by the fact that the main villain was hidden in plain sight, throwing off everyone, myself included, and turning the genre upside down as well as creating one of the better baddies in Disney. It was a controversial decision as children were upset, but an important one, defended by those who said that children need to be aware of shifts in personality.

By a strange coincidence another instance of hoodwinking via predictability, also aimed at a younger market, can be seen in the complete opposite: with the true hero being hidden.

Remember at the beginning the character who self-sacrifices? Take the same idea, a person loathing the hero but then willingly dying to save them, do the usual deflection by putting it into a setting that seems new and fresh, like a school of magic. Build this character so even the readers hate him and want him to die a horrible death, then twist it so that when he dies, obviously helping the person he hates, he truly becomes the real hero of the story. Yes, of course, it is Severus Snape in the Harry Potter saga. Snape, in fact, had, over the course of seven books, multiple storylines. He is the bullied nerd at school, he suffers the fate of unrequited love, and this obsession—and the knowledge that he will never find true love—drives him and makes him feasible; he becomes the bully, he is a double agent and manipulated by both sides. The author may currently not be flavour of the year, but her Snape plot line is a brilliant tour de force when it comes to deflecting, or spinning, predictability and conventions back onto the reader by using them as a red herring.

As seen, predictability aids the reader in many aspects—even to the choice of material to be consumed. For the storyteller it raises different issues. It often needs to be there, depending on genre, but it also acts as a tool to be used and, as with Shakespeare and Hathaway, abused. In a writer’s bid to bend or thwart predictability, it drives and pushes creativity. With seemingly limited options one can rise to the occasion and write their way out of anything, giving the illusion that it is fresh and original; therefore, purely trying to defeat predictability makes it a storytelling necessity. Predictability is, indeed, powerful.

__________________________

Full interview with Veronica Henry

© Michael Garry Smout 2022

This essay may not be archived, reproduced or distributed further without the author's express permission.

Please see our conditions of use.

The Barcelona Review is a registered non-profit organization